The 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans are out, and social media is in a tizzy over them.

According to the internet, everything you thought you knew about nutrition is wrong now. Butter is back. Carbs are cancelled. Protein is most definitely the main character. And somehow, the food pyramid is trending again (even though we haven’t actually used it since 2011).

If your feed feels chaotic, you’re not imagining it. Mine looked like two very different conversations happening at the same time.

On one side, people in my professional space. Registered Dietitians, science communicators, physicians, public health experts, etc shared a lot of very specific frustrations:

- Anger at the current administration and how politicized this rollout feels

- Confusion and annoyance over replacing MyPlate with an upside-down pyramid

- “We haven’t used the food pyramid in 15 years. Why are we back here?”

- Strong reactions to the saturated fat messaging

- Complaints that fiber barely gets a moment

- Concerns about conflicts of interest among people involved in shaping the guidelines

Then there’s the other side of the internet. And yes, I look there too.

Accounts that have spent years telling people not to trust government nutrition guidance were suddenly thrilled. According to them, this update proves that calories don’t matter, carbs are the problem, meat is the solution, butter and beef tallow are vindicated, and “real food” has finally won.

Same document. Completely different interpretations.

That disconnect is the heart of the problem.

Most of the reaction has very little to do with what the guidelines actually say, and everything to do with how they’re being framed, clipped, politicized, and turned into internet-friendly soundbites.

Before reacting or rewriting your grocery list, it’s worth slowing down and looking at what’s actually in the guidelines, what stayed the same, and what really changed compared to previous versions.

Because the reality is a lot less dramatic than your feed would have you believe.

A quick reality check: what dietary guidelines are (and are not)

Before we go any further, let’s get clear on what the Dietary Guidelines are meant to be.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans provide general nutrition guidance for Americans as a whole. They help shape policies and programs that affect millions of people at once, while also offering broad direction for individuals.

What they are not meant to be is individualized health advice.

In other words, they’re designed to point people in the right direction, not tell you exactly what to eat, how much to eat, or what’s right for your specific body.

At their core, the guidelines:

- Offer general nutrition recommendations meant to apply to most Americans

- Are updated every five years (since 1980)

- Help shape public health messaging, school meal standards, and federal nutrition programs.

What they don’t do is:

- Function as a personalized nutrition plan

- Account for your medical history, preferences, or lifestyle, or relationship with food

- Replace individualized guidance from a Registered Dietitian

That gap between what the guidelines are designed to do and how people interpret them helps explain why reactions to this update are so divided.

And that split is only amplified by how the update is being framed. The rollout language positions the new guidelines as a major reset and a return to basics, which naturally signals a break from the past.

To understand whether that’s actually true, we need to zoom out and look at how the guidelines have evolved over time.

A brief history of the Dietary Guidelines (and why this matters)

A big reason this update feels dramatic is because most people don’t actually know how long the Dietary Guidelines have been around.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans were first released in 1980, and they’ve been updated every five years since. From the very beginning, they were built around a small set of core principles that continue to show up, in one form or another, across every update.

1980: the original guidelines

The first Dietary Guidelines for Americans introduced seven core principles:

- Eat a variety of foods: The guidelines explicitly stated that no single food supplies all essential nutrients. A mix of fruits, vegetables, whole and enriched grains, dairy, and protein foods like meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and legumes were encouraged.

- Maintain ideal body weight: Even in 1980, the guidelines linked higher body weight with conditions like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, heart attack, and stroke.

- Avoid too much fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol: This section is often misrepresented in hindsight. The guidelines noted that saturated fat and cholesterol raise blood cholesterol in most people, but the emphasis was on moderation, not elimination. Foods like eggs and organ meats were acknowledged as both nutrient-dense and sources of cholesterol, and whole milk was not banned. Instead, the guidance focused on balancing fat intake across the overall diet.

- Eat foods with adequate starch and fiber: Carbohydrates were emphasized as a primary energy source, particularly in the context of reducing fat intake. The guidelines pointed out that carbohydrates provide fewer calories per ounce than fat and encouraged complex carbohydrate sources over simple sugars to increase fiber intake.

- Avoid too much sugar: At the time, the primary concern around sugar was dental health rather than weight gain or metabolic disease.

- Avoid too much sodium: Sodium intake was already recognized as a concern, particularly for individuals with high blood pressure.

- If you drink alcohol, do so in moderation: Alcohol was described as high in calories and low in nutrients, with excessive intake linked to vitamin and mineral deficiencies. The guidelines stated that one to two drinks per day did not appear to cause harm for most adults. Guidance around pregnancy reflected the evidence available at the time. Pregnant women were advised to limit alcohol intake to 2 ounces or less on a single day, rather than avoid it entirely.

Taken together, these recommendations established the blueprint that future guidelines would build on. The emphasis on variety, moderation, energy balance, fiber-rich carbohydrate sources, and limits on saturated fat, sugar, sodium, and alcohol was present from the very beginning.

1985-1990: same principles, clearer language

The 1985 guidelines kept the same seven principles. The updates were largely about clarity and wording, rather than a significant shift in philosophy.

1990: language shifts and added specificity

The 1990 guidelines introduced subtle but important changes in how recommendations were framed.

- “Eat foods with adequate starch and fiber” shifted to “choose a diet with plenty of vegetables, fruits, and grain products.”

- “Avoid too much sugar” and “avoid too much sodium” became “use sugars only in moderation” and “use salt and sodium only in moderation.”

Alcohol guidance was also refined:

- Women who were pregnant or trying to conceive were advised not to drink

- Sex-specific guidance appeared, with one drink per day for women and two for men

- Additional situations were outlined where alcohol should be avoided entirely

The underlying principles remained consistent.

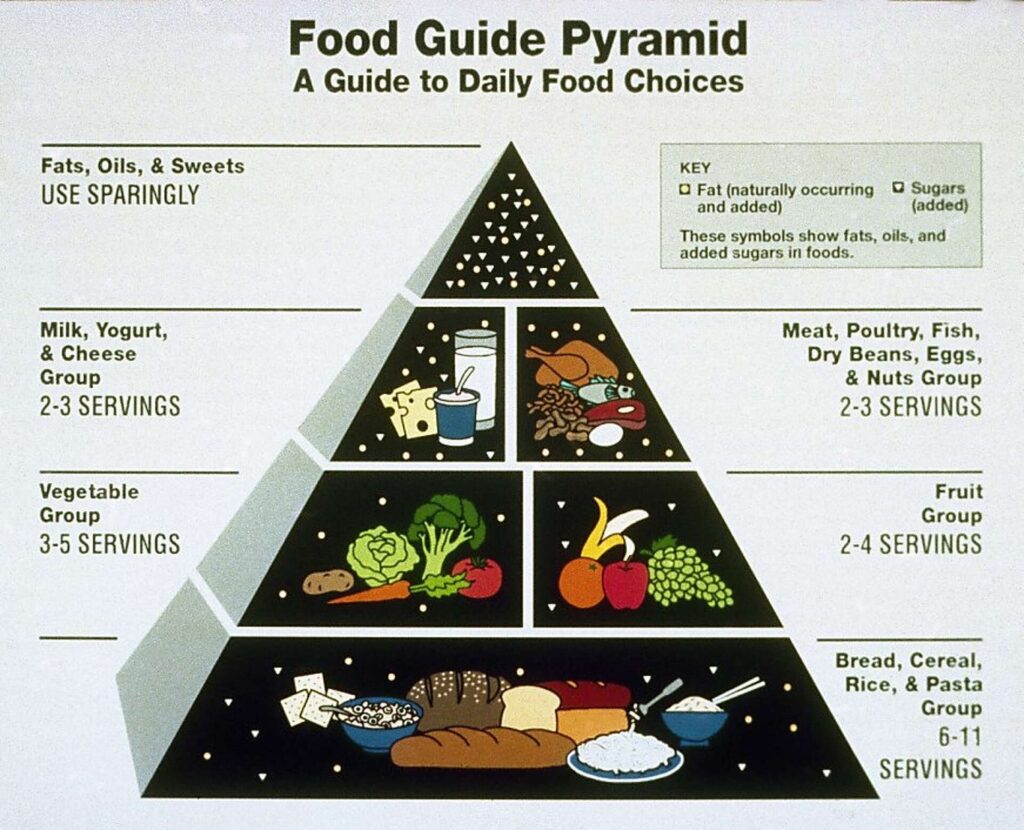

1992: Introducing the Food Guide Pyramid

In 1992, the USDA introduced the Food Guide Pyramid as a visual tool to help translate the Dietary Guidelines into something more consumer-friendly.

The pyramid was not a new set of recommendations. It was a graphic representation of existing guidance, designed to show relative proportions of food groups and suggested daily servings.

The structure had four levels:

- Base: bread, cereal, rice, and pasta (6 to 11 servings per day)

- Second level: vegetables (3 to 5 servings) and fruits (2 to 4 servings)

- Third level:

- milk, yogurt, and cheese (2 to 3 servings)

- meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs, and nuts (2 to 3 servings)

- Top: fats, oils, and sweets, labeled “use sparingly”

The pyramid shape was intentional. The wider base signaled foods to eat more often, while the narrow top indicated foods to eat less frequently.

All this to say, the Food Guide Pyramid certainly wasn’t perfect.

It grouped foods by category rather than nutrient quality. All carbohydrates were treated similarly, without distinction between refined and whole grains. Fats were placed at the top as a group, despite differences between saturated and unsaturated fats. Foods were assigned to single categories, even though most foods contain multiple nutrients.

The pyramid has also been criticized for it’s heavy emphasis on grain-based foods. Some of that criticism reflects broader concerns about the USDA’s dual role in both promoting U.S. agriculture while issuing national nutrition guidance. While there’s no evidence that any single industry dictated the pyramid’s design, agricultural priorities, food availability, and cost considerations were part of the policy context in which it was developed.

1995: Building on the pyramid

The 1995 guidelines expanded earlier recommendations and explicitly positioned the Food Guide Pyramid as the primary tool for applying them.

This update focused less on introducing new nutrition concepts and more on making the guidance actionable, including:

- Clearer definitions of servings

- Recognition of vegetarian and vegan diets as nutritionally adequate when well planned

- The first inclusion of physical activity guidance as part of overall health.

- Continued emphasis on grains, fruits, vegetables, fiber, and low saturated fat intake

- A low-fat dietary pattern remained central with recommendations to limit saturated fat to less than 10% of total calories and dietary cholesterol to <300 mg per day

- Sugar substitutes were permitted

- Sodium intake was recommended at less than 2,400 mg per day

- Alcohol guidance remained relatively unchanged

2000: Refining the message

The 2000 Dietary Guidelines largely reinforced existing recommendations, but introduced more precise language and a clearer framework for applying them.

The guidelines were organized around three themes: Aim for fitness, Build a healthy base, and Choose sensibly. Physical activity was further elevated, with daily movement emphasized for weight management and chronic disease prevention.

Nutrition guidance sharpened in several areas. Whole grains were more clearly prioritized over refined grain products, distinctions between saturated fat limits and moderation of total fat were clarified, and beverages were explicitly identified as a source of added sugars. The update also expanded guidance on food safety, including proper handling, storage, and preparation.

2005: A more technical turn and a focus on energy balance

The 2005 Dietary Guidelines marked a shift in tone and audience. Compared to earlier editions, this version functioned less as a public-facing guide and more as a technical policy document for healthcare professionals and educators.

Energy balance moved to the center of the guidance. Weight management was framed explicitly as the relationship between calories consumed and calories expended, with physical activity integrated directly into nutrition recommendations. General encouragement to “be active” was replaced with goal-based targets tied to disease prevention, weight maintenance, and weight loss.

Several nutrient-specific updates also appeared. Trans fats were addressed for the first time, with guidance to keep intake as low as possible. Whole grains were more clearly prioritized over refined grains. Sodium recommendations became more targeted, advising no more than 1,500 mg per day for certain higher-risk groups and less than 2,300 mg per day for the general population. Added sugars received increased scrutiny in the context of overall calorie balance.

This edition also introduced the concept of “discretionary calories,” acknowledging that once nutrient needs are met through nutrient-dense foods, a limited number of remaining calories could come from added fats or sugars.

And notably, MyPyramid replaced the original Food Guide Pyramid in an attempt to reflect personalization and physical activity, though it was widely criticized for being difficult to interpret.

2010: Urgency, patterns, and the food environment

The 2010 Dietary Guidelines reflected a growing sense of urgency around rising obesity rates and diet-related chronic disease. The focus expanded beyond individual choice to include the broader “obesogenic” environment shaping how Americans eat.

Several notable updates emerged. The guidelines placed stronger emphasis on maintaining calorie balance over time to reach and sustain a healthy weight. Solid fats and added sugars were increasingly discussed together as a major source of excess calories with limited nutrient value.

For the first time, quantitative seafood recommendations were introduced, advising at least 8 oz of seafood per week for the general population and 8–12 oz per week of lower-mercury seafood for pregnant and breastfeeding women. Vegetable guidance was also refined, with explicit emphasis added for red and orange vegetables alongside dark-green vegetables and beans and peas. Replacing refined grains with whole grains received increased attention.

Fortified soy beverages were formally included in the dairy group, reflecting their nutritional similarity to cow’s milk.

The guidelines also more explicitly adopted a social-ecological perspective, acknowledging that eating behaviors are influenced not only by personal decisions but by food environments (such as schools and workplaces), sectors of influence (including government, industry, and media), and social and cultural norms.

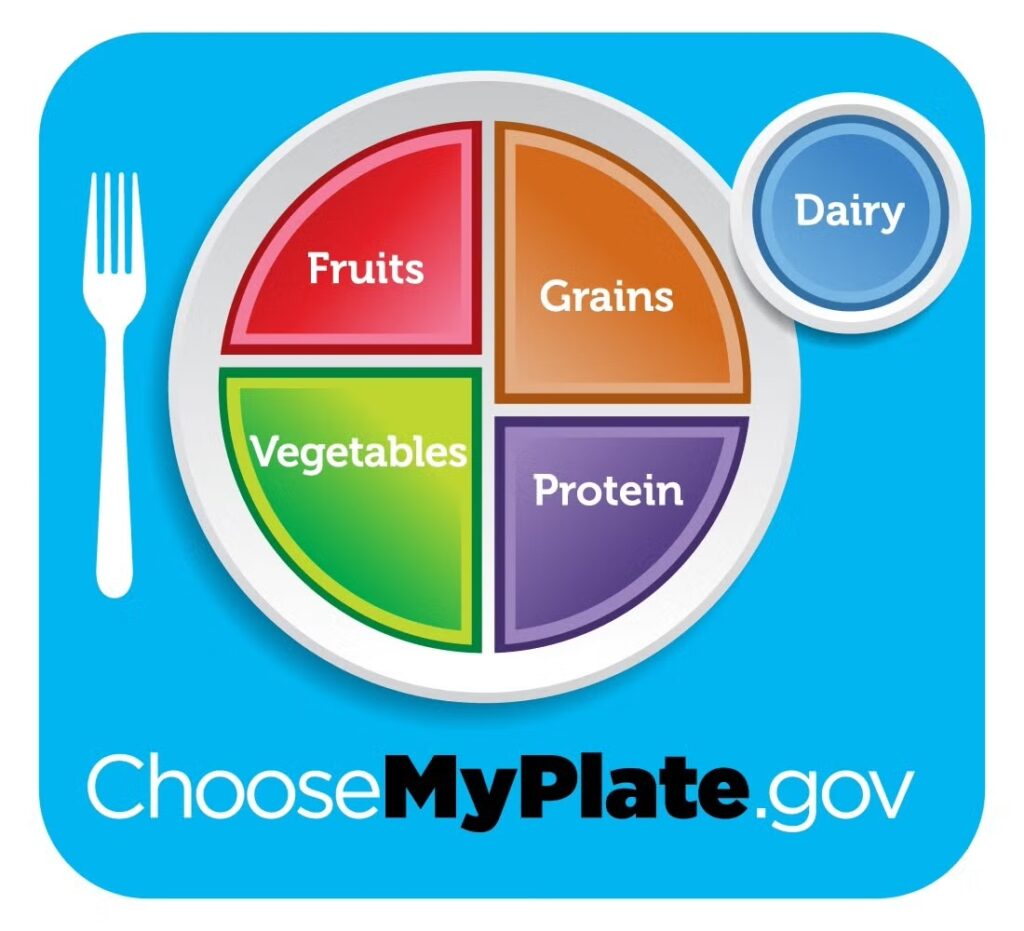

2011: Enter MyPlate

In 2011, the USDA replaced MyPyramid with MyPlate, a new visual model designed to simplify how dietary guidance was communicated to the public.

Unlike the pyramid, MyPlate moved away from abstract serving ranges and instead focused on proportions. The graphic showed a plate divided into four sections for fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and protein, with a small circle representing dairy placed to the side.

MyPlate was meant to be intuitive, practical, and easier to apply at mealtime, without requiring people to calculate servings or remember numeric targets. The visual emphasized filling half the plate with fruits and vegetables, one quarter with protein, and one quarter with grains.

2015: Eating patterns take center stage

The 2015 Dietary Guidelines built directly on the 2010 edition but sharpened the focus on overall eating patterns rather than individual nutrients or foods.

Several notable updates followed. For the first time, a quantitative limit on added sugars was introduced, recommending intake remain below 10% of total daily calories, replacing earlier “moderation” language. At the same time, dietary cholesterol was no longer identified as a nutrient of concern for overconsumption, reflecting updated evidence on its impact for most people.

Limits on saturated fat remained in place at less than 10% of total calories. Sodium guidance was simplified to a single primary target of less than 2,300 mg per day for individuals aged 14 and older, while noting that people with hypertension or prehypertension could benefit from lower intakes closer to 1,500 mg per day.

The guidelines also clarified that moderate coffee consumption, defined as three to five 8-ounce cups per day (up to about 400 mg of caffeine), was compatible with a healthy eating pattern. Language around alcohol moderation was tightened, with clearer limits and stronger acknowledgment of associated health risks.

2020: A lifespan approach

The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines reinforced the pattern-based framework introduced in 2015, but for the first time since 1985, the guidelines included specific recommendations for infants and toddlers from birth to 23 months and pregnancy and lactation. Previous editions focused primarily on individuals aged 2 years and older.

With the inclusion of the earliest life stages, several new directives were introduced. Exclusive breastfeeding was recommended for about the first six months of life, with zero added sugars advised for infants and toddlers under age 2. Early allergen introduction, including foods such as peanuts and eggs, was encouraged alongside complementary foods around six months.

The 2020 guidelines also adopted the theme “Make Every Bite Count” to emphasize nutrient density. The premise was that once nutrient needs are met, most people have relatively few discretionary calories available, making food choices more consequential. Healthy eating was framed as a flexible, adaptable pattern intended to reflect cultural traditions, personal preferences, and budget rather than a rigid prescription.

What did not change. Added sugars remained capped at less than 10% of daily calories, saturated fat at less than 10% of daily calories, and alcohol limits at up to one drink per day for women and two for men.

Taken together, this history shows a set of guidelines that have evolved gradually, not abruptly. As new evidence emerged, language was refined, frameworks were updated, and emphasis shifted, but the core themes remained remarkably consistent over time.

Why dietary guidelines evolve over time

There’s a tendency to read any update to the Dietary Guidelines as an admission of failure. As if a change automatically means the old guidance was wrong.

In reality, the guidelines evolve as nutrition science advances and as the health needs of the population change.

A larger body of evidence

When the first Dietary Guidelines were released in 1980, nutrition science was less robust than it is today. We didn’t have decades of long-term studies, large population datasets, or repeated trials examining the same questions from multiple angles.

Forty-five years later, we have more evidence and a better understanding of how dietary habits play out over time and across populations. As that evidence base grows, guidance becomes more specific.

The food environment changes

The way Americans eat today differs significantly from how we ate in 1980, or even 2000. Portion sizes are larger, ultra-processed foods are more prevalent, and added sugars show up in places they didn’t before. Convenience, cost, and availability now play a larger role in shaping food choices.

As the food environment shifts, the guidelines adjust to reflect the reality people are navigating, rather an idealized version of how eating “should” look.

Population health needs shift

The health profile of the U.S. population has changed alongside the food supply. The population is older, rates of obesity and metabolic disease are higher, and physical inactivity is more common. Muscle loss, chronic disease management, and weight-related medications are now part of routine care in ways they were not decades ago.

Nutrition guidance evolves to reflect those changing priorities, even when the underlying principles remain familiar.

Taken together, these shifts help explain why the Dietary Guidelines change over time without representing a complete departure from what came before.

Why the 2025 update feels bigger than it is

A big reason the 2025 Dietary Guidelines have caused so much whiplash isn’t because the recommendations are dramatically different.

It’s because of how they were presented.

The rollout language positioned this update as a “reset.” A return to basics. A course correction. Visual choices like bringing back a pyramid-style graphic reinforced the impression that something fundamentally new or old was happening.

When people hear “reset,” they assume reversal. They assume what came before failed. They assume they’ve been misled.

But this assumption doesn’t hold up when you look at the document itself.

Most of what the guidelines emphasize in 2025 has been emphasized for decades. What changed most wasn’t the science, but the messaging around it.

And because most people experience nutrition guidance through headlines, graphics, and social media clips rather than policy documents, the messaging matters.

Add in a politicized environment, deep distrust of institutions, and an algorithm that rewards clickbait and outrage content, and suddenly the same document ends up being interpreted in completely opposite ways.

Either as proof that the government finally “got it right,” or proof it’s completely lost the plot.

Neither is true.

To understand what this update actually means, we have to separate the presentation from the substance.

So let’s do that next, shall we?

What the 2025 Dietary Guidelines actually say

To make sense of the 2025 update, it helps to separate three things that have been blurred together online:

- What the recommendations actually say

- What changed versus what stayed the same

- How the guidelines were presented

Instead of getting lost in the politics of it all, let’s look at what the guidelines actually say, based on the language and materials put forward by the current administration.

What stayed the same

Before getting into what’s new, it’s worth grounding ourselves in what didn’t change. Because despite the dramatic rollout, much of the foundation of the Dietary Guidelines is still very familiar.

The foundations remain intact:

- Energy intake still matters. Both the 2020 and 2025 Dietary Guidelines emphasize aligning intake with individual energy needs, based on factors like age, sex, body size, and activity level. The idea that healthy eating includes appropriate portions, not just food choices, did not change.

- Saturated fat remains capped at less than 10% of daily calories. This limit has been in place for decades and remains unchanged. What did change is how certain saturated fat–rich foods are discussed and emphasized, which has contributed to confusion and strong reactions. We’ll unpack that in the next section.

- Added sugars are still recommended to be limited. Keeping added sugars low remains a core principle, even as the way those limits are defined and discussed has evolved.

- Fruits and vegetables remain foundational. This recommendation has been consistent since the first guidelines in 1980.

- Whole grains are still prioritized over refined grains. The emphasis on fiber-rich, minimally refined carbohydrate sources remains.

- Ultra-processed foods are still discouraged. While the language now leans more heavily on “real food,” the underlying message has been present for years: diets dominated by highly processed foods are associated with poorer health outcomes.

- The lifespan approach remains in place. The guidelines continue to provide stage-specific recommendations from infancy through older adulthood.

- The general sodium limit stayed the same. For the general population ages 14 and older, the target remains less than 2,300 mg per day.

- Early allergen introduction guidance did not change. Introducing potentially allergenic foods like peanuts, eggs, and wheat around six months remains recommended.

- The overall message to limit alcohol intake remains. While specific numeric limits are less prominent in the 2025 materials, the overall message to limit alcohol intake remains.

With that baseline established, let’s talk about what actually changed.

What changed in the 2025 Dietary Guidelines

Now that we’ve reviewed what stayed the same, we can look at what actually changed in the 2025 update.

A return to the food pyramid

One of the most visible changes in the 2025 Dietary Guidelines is the reintroduction of a pyramid-style graphic.

In the opening note of the guidelines, the administration states:

“Under President Trump’s leadership, we are restoring common sense, scientific integrity, and accountability to federal food and health policy—and we are reclaiming the food pyramid and returning it to its true purpose of educating and nourishing all Americans.”

For context, the food pyramid has not been used in federal dietary guidance since 2011, when MyPlate replaced MyPyramid as the primary visual model. MyPlate organized guidance around meal composition, using proportional sections of fruits, vegetables, grains, protein, and dairy.

The 2025 update moves away from that format and returns to a pyramid-style model, inverted so that foods emphasized most prominently appear at the top rather than the base. This pyramid is presented as the primary visual framework for the guidelines, replacing MyPlate.

Importantly, this represents a shift in visual communication rather than a wholesale rewrite of the underlying recommendations. Many of the recommendations reflected in the 2025 pyramid have existed for years, even though the framing looks different.

Protein foods

The 2025 Dietary Guidelines introduce explicit bodyweight-based protein targets, which were not included in the 2020 guidelines.

In the 2025 guidance, protein intake is framed as a priority at every meal, with the following quantitative recommendation:

“Protein serving goals: 1.2–1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, adjusting as needed based on your individual caloric requirements.”

*This translates to approximately 0.54–0.73 grams of protein per pound of body weight per day.*

By contrast, the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines expressed protein needs using ounce-equivalents per day based on calorie level (for example, 5.5 oz-eq at 2,000 calories), without providing gram-per-bodyweight target.

Beyond the new quantitative guidance, the 2025 guidelines place stronger emphasis on prioritizing protein foods at every meal, consuming a variety of protein sources from both animal and plant foods, and choosing protein options with minimal added sugars and refined carbohydrates. Cooking methods such as baking, roasting, grilling, broiling, and stir-frying are favored over deep-frying.

Taken together, the shift toward explicit gram-based targets and stronger prioritization language represents a meaningful change in how protein intake is framed compared to the 2020 guidelines.

Dairy

The 2025 Dietary Guidelines retain the same quantitative intake target for dairy as previous editions, but change how dairy is described and prioritized.

The recommended intake remains three servings of dairy per day, adjusted as needed based on individual caloric requirements.

In the 2020–2025 guidelines, low-fat and fat-free dairy were explicitly emphasized, with lactose-free dairy and fortified soy beverages repeatedly referenced as nutritionally comparable alternatives. Dairy guidance focused on meeting calcium, vitamin D, and protein needs through a range of options.

In the 2025 guidelines, full-fat dairy is explicitly emphasized. Guidance centers on foods such as milk, yogurt, and cheese without prioritizing reduced-fat versions. Lactose-free and dairy-free alternatives receive less prominence in the core recommendations, and fortified soy beverages are no longer highlighted as direct dairy equivalents.

The shift away from emphasizing low-fat, lactose-free, or non-dairy substitutes represents a change in how dairy is positioned, even though the daily serving recommendation itself did not change.

Gut Health

Gut health is a newly emphasized category in the 2025 Dietary Guidelines as a distinct component of overall health.

While previous editions discussed fiber and digestive health indirectly, the 2025 guidelines explicitly introduce gut health as a distinct concept tied to overall health.

While prior editions addressed fiber and digestive health indirectly, the 2025 guidelines explicitly frame gut health as a pattern-level outcome supported by dietary variety and food quality. The guidance emphasizes consuming a wide range of whole foods, prioritizing fiber-rich foods from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans, peas, and legumes, and including fermented foods such as sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, and miso as part of a healthy dietary pattern.

Notably, this section does not introduce quantitative intake targets, such as specific grams of fiber or servings of fermented foods. Instead, gut health is positioned as an outcome of consistent dietary patterns rather than a metric to be optimized.

Fruits and Vegetables

The 2025 Dietary Guidelines continue to position fruits and vegetables as foundational to a healthy dietary pattern, but the way intake targets are expressed has changed.

In the 2020 guidelines, fruit and vegetable recommendations were presented as cup-equivalents per day based on calorie level. In the 2025 guidelines, intake is expressed using servings per day: three servings of vegetables and two servings of fruit.

The 2025 guidelines define a serving as 1 cup of raw or cooked vegetables (or 2 cups of leafy greens) and 1 cup of fresh, frozen, or canned fruit (or ½ cup dried fruit).

When these serving definitions are applied, the total recommended intake is broadly consistent with prior guidance, though presented using different terminology.

The shift reflects a change in terminology and communication rather than a change in emphasis or overall intake.

Fats and Oils

The quantitative limit on saturated fat remains unchanged between the 2020 and 2025 Dietary Guidelines. Intake is still recommended to remain below 10% of total daily calories. What changed is the surrounding guidance on fat sources, substitutions, and practical strategies.

In the 2025 guidelines, oils are no longer assigned a specific daily intake target. In prior editions, oils were listed quantitatively (for example, 27 grams per day at the 2,000-calorie level). In 2025, oils are discussed qualitatively rather than as a numeric goal.

Fats are framed primarily through food examples rather than substitution strategies. The guidance emphasizes that “healthy fats” are found in whole foods such as meats, poultry, eggs, omega-3–rich seafood, nuts, seeds, full-fat dairy, olives, and avocados. When cooking or adding fats to meals, the guidelines advise prioritizing oils with essential fatty acids, such as olive oil (side note: olive oil isn’t a good source of essential fatty acids, but we’ll get to that later), while also noting that butter or beef tallow can be used.

Notably, the 2025 guidelines do not include explicit recommendations to replace saturated fats with unsaturated fats, a strategy that was emphasized in prior editions. Dietary cholesterol and trans fats are also not addressed in the 2025 guidance. The document states that more high-quality research is needed to determine which types of dietary fats best support long-term health.

While the saturated fat cap itself did not change, the framing and emphasis around fats and oils represent a meaningful shift compared to earlier guidelines.

Grains

Grain recommendations changed in both structure and emphasis between the 2020 and 2025 Dietary Guidelines.

Whole grains continue to be recommended as part of a healthy dietary pattern, with fiber-rich carbohydrate sources prioritized. What changed is how intake targets are defined.

In the 2025 guidelines, whole grains are the only grain category with specified intake targets, set at 2–4 servings per day, adjusted based on individual caloric needs. Refined grains are no longer assigned a daily allowance and are explicitly discouraged. Unlike prior editions, which allowed a portion of total grain intake to come from refined grains, the 2025 guidance does not include refined grains within recommended intake targets

Highly Processed Foods, Added Sugars and Refined Carbohydrates

In the 2025 Dietary Guidelines, highly processed foods, added sugars, and refined carbohydrates are addressed together under a single recommendation, rather than as separate concerns.

What stayed the same

Dietary patterns high in processed foods, added sugars, and refined carbohydrates continue to be discouraged due to their association with poorer health outcomes. Prior editions addressed these concerns primarily through individual nutrient limits (such as added sugars or saturated fat), but the overall message to limit these foods has been consistent.

What changed in 2025

- Highly processed foods: The 2025 guidelines use more direct language to discourage consumption of highly processed packaged, prepared, or ready-to-eat foods, particularly those that are salty or sweet. Examples explicitly listed include chips, cookies, candy, and similar products. The guidance emphasizes prioritizing nutrient-dense foods and home-prepared meals, including when dining out.

- Added sugars: Added sugars receive more specific and restrictive guidance in 2025 than in prior editions. The guidelines state:

- No amount of added sugars or non-nutritive sweeteners is recommended or considered part of a healthy or nutritious diet.

- One meal should contain no more than 10 grams of added sugars.

- Snack guidance is also more prescriptive, aligning added sugar limits with FDA “Healthy” claim thresholds. For example, grain-based snacks should not exceed 5 grams of added sugar per ¾ ounce whole-grain equivalent, and dairy-based snacks should not exceed 2.5 grams of added sugar per ⅔ cup equivalent.

- Non-nutritive sweeteners: Low-calorie non-nutritive sweeteners are explicitly discouraged in the 2025 guidance. Foods and beverages containing artificial sweeteners such as aspartame, sucralose, saccharin, xylitol, and acesulfame potassium are included among items to limit.

- Refined carbohydrates: The 2025 guidelines advise significantly reducing intake of highly processed refined carbohydrate foods, such as white bread, packaged breakfast products, flour tortillas, and crackers. This recommendation appears alongside the added sugars and highly processed foods guidance, rather than as a standalone grain-specific limit.

Alcohol

Alcohol guidance changed notably in the 2025 Dietary Guidelines, primarily through what was removed rather than what was added.

The 2025 guidelines continue to state that alcohol is not necessary for health and that limiting alcohol intake is part of a healthy dietary pattern.

What changed is the removal of quantitative drink limits. Unlike the 2020–2025 guidelines, which specified limits such as up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men, the 2025 guidance does not include daily or weekly numeric thresholds. Alcohol is framed more generally as something to limit, without defining a specific amount.

Sodium and electrolytes

The 2025 Dietary Guidelines retain the long-standing sodium limits while adding new language around electrolytes and hydration.

For the general population ages 14 and older, the recommended sodium limit remains less than 2,300 mg per day, and highly processed foods high in sodium continue to be discouraged.

What changed in 2025 is how sodium is discussed. The guidelines explicitly pair sodium with electrolytes and hydration, describing sodium as essential for fluid balance rather than focusing solely on its role as a nutrient to limit. The document also acknowledges that highly active individuals may require higher sodium intake to offset sweat losses.

Sodium recommendations for children are clearly outlined by age group:

- Ages 1-3: less than 1,200 mg per day

- Ages 4-8: less than 1,500 mg per day

- Ages 9-13: less than 1,800 mg per day

The sodium targets did not change, but the 2025 guidelines add new language around electrolytes and hydration.

Social, Cultural, and Access Considerations

In the 2020 Dietary Guidelines, there was explicit acknowledgment that food choices are shaped by factors beyond individual preference, including culture, budget, food access, and environmental context.

In contrast, this type of framing is largely absent from the 2025 Dietary Guidelines. The document does not include a dedicated focus on cultural foodways, socioeconomic constraints, or structural barriers to healthy eating, nor does it offer guidance on adapting recommendations based on access or affordability.

This shift reflects a change in scope rather than a change in nutrient recommendations. The dietary advice itself remains broadly similar, but the framing moves away from addressing the broader social and environmental context in which food choices are made.

How I’m Interpreting the 2025-2030 Guidelines as a Registered Dietitian

Before I jump into any “hot takes”, I want to be clear about how I’m looking at this update.

I’m not reading the 2025 Dietary Guidelines as a culture war document.

I’m also not pretending they exist outside of politics.

Both things can be true.

This update didn’t land in a vacuum. The language, visuals, and rollout were intentionally framed as a correction. A return. A reclaiming. That framing matters because it primes people to believe something went wrong before and that we’re finally fixing it now.

That’s why the internet split so fast.

If you already distrust government nutrition guidance, this felt like vindication.

If you work in public health or nutrition, it felt confusing, rushed, and oddly familiar at the same time.

As a Registered Dietitian, my job here isn’t to pick a team. It’s to separate:

- What the guidelines actually recommend

- How those recommendations are being packaged

- And where the gaps or contradictions show up when you look closely

No guideline is free from bias. No reviewer is either. Including me.

So instead of asking whether these guidelines are “good” or “bad,” I’m asking a more useful question:

What do these guidelines do well, where do they fall short, and who is most affected by those choices?

If that sounds less dramatic than your feed, good. That’s the point.

So let’s get into my thoughts…

“Real food” is doing a lot of rhetorical work here

One thing that jumps out immediately in the 2025 guidelines is how often the concept of “real food” is implied, if not outright stated.

This isn’t new advice. It’s just being framed differently.

“Real food” sounds obvious. Of course we should eat real food. Who’s going to argue with that?

But the problem is, “real food” is not a scientific term.

It’s a value-laden phrase that carries moral weight without having a clear, standardized definition.

In the 2025 guidelines, “real food” becomes shorthand for a whole cluster of ideas:

- less processing

- fewer ingredients

- fewer additives

- more cooking at home

- more animal-based protein

- fewer packaged foods

Some of those ideas are supported by evidence. Some are context-dependent.

When guidance shifts from nutrient-based language to moralized categories like “real” versus “processed,” it changes how people hear the message. It stops sounding like neutral public health guidance and starts sounding like a judgment about how people eat.

It also explains why the pyramid imagery lands the way it does. A pyramid visually reinforces hierarchy. What’s at the top looks “best.” What’s lower looks suspect. That framing pairs neatly with “real food” rhetoric, even if the written guidance underneath is more complicated.

None of this means prioritizing minimally processed foods is wrong.

It means the language choice matters, especially when you’re speaking to a population that already feels confused, defensive, or burned by nutrition advice.

And this is where the gap between science and messaging starts to widen.

The removal of equity language isn’t neutral, even if it’s framed as “scientific purity”

Compared to 2020, the 2025 Dietary Guidelines largely remove explicit discussion of social determinants of health, food access, affordability, and structural barriers to healthy eating.

This wasn’t an accident.

In accompanying materials, the administration has been very clear about the rationale. Their position is that scientific evaluation should occur independently of equity considerations, and that factors like race, income, culture, and access should be addressed downstream in policy implementation, not embedded in the science itself.

On paper, that sounds clean. Neutral. Objective.

In practice, it’s not that simple.

Nutrition science does not exist in a vacuum. When guidance is written as if everyone has equal access, equal time, equal money, and equal food environments, it implicitly centers the experience of people who already do.

The 2020 guidelines explicitly acknowledged that food choices are shaped by:

- income and food prices

- access to grocery stores and cooking facilities

- cultural food traditions

- time, labor, and caregiving demands

The 2025 guidelines largely step away from that framing, narrowing the lens back toward individual food choices and “optimal” patterns, without the same acknowledgment of the constraints many people are operating under.

That matters, especially when the document simultaneously cites alarming population-level statistics about obesity, diabetes, and chronic disease.

You can’t have it both ways.

You can’t emphasize worsening health outcomes at a population level and then strip away the context that helps explain why those outcomes exist and who is most affected.

This isn’t about defending DEI language for the sake of it. It’s about recognizing that nutrition guidance doesn’t just describe what people should eat. It implicitly communicates who the guidance is for.

Framing this shift as a return to “unbiased science” also deserves scrutiny. All science involves choices: what questions are asked, what outcomes are prioritized, what evidence is considered relevant. Deciding that equity considerations belong “later” is still a value judgment.

And for the people most affected by food insecurity, limited access, chronic disease, or economic constraints, this shift isn’t theoretical. It changes how guidance gets translated, funded, enforced, and supported.

Whether intended or not, narrowing the scope of the guidelines narrows who they meaningfully serve.

The implementation vs interpretation gap

A piece of this conversation that’s getting almost no attention online is the difference between interpreting the guidelines and implementing them.

The Dietary Guidelines directly inform how food is purchased, prepared, and served in large-scale systems, including:

- School meal programs

- WIC

- SNAP-Ed

- Federal food procurement standards

- Institutional food service (hospitals, prisons, VA systems, long-term care)

These systems don’t run on intuition or “common sense.”

They run on numeric standards, definitions, and thresholds.

Moving away from clear substitution guidance, like explicitly recommending replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats, removes a practical lever that programs rely on to meet nutrient targets while staying within budget and procurement rules.

Similarly, using the term “highly processed” without a standardized scientific definition creates implementation challenges. Schools and federal programs can’t operationalize a concept that isn’t clearly defined in measurable terms. They need to know:

- Does this food qualify or not?

- What criteria are being used?

- How is compliance evaluated?

“Highly processed” may resonate emotionally with the public, but it’s much harder to translate into policy compared to nutrient-based thresholds like grams of added sugar, sodium limits, or whole grain percentages.

The same issue shows up with fats. The saturated fat cap is still there, but the surrounding guidance is less directive. When foods like butter, beef tallow, red meat, and full-fat dairy are highlighted without equally clear guidance on tradeoffs or substitutions, it leaves implementers with mixed signals which ultimately slow programs down, create inconsistencies, and make enforcement harder.

None of this means the guidelines are unusable. It means that some of the shifts that feel cosmetic or rhetorical online carry disproportionate weight in real-world settings.

For an individual reading the guidelines casually, ambiguity might feel freeing but for institutions feeding millions of people, ambiguity is a problem.

“Ending the war on protein” (what war??)

Let’s start with where I agree.

I’m broadly supportive of the higher protein intake ranges emphasized in the 2025 Dietary Guidelines. They’re not revolutionary but they better reflect how protein is actually used in clinical practice.

For years, most official protein recommendations have been anchored to the RDA, or Recommended Dietary Allowance. The RDA for protein is 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day (about 0.36 g per pound). It’s important to understand what that number is and what it isn’t.

The RDA is not an optimal intake target.

It represents the minimum amount of protein needed to prevent deficiency in most healthy adults. It’s a floor, not a goal.

That’s why many Registered Dietitians, myself included, have recommended higher protein intakes for years, especially for:

- People pursuing fat loss

- Active individuals

- Adults concerned with muscle preservation

- People on GLP-1 medications

- Individuals with higher satiety needs

The 2025 guidelines move closer to this reality by introducing updated protein targets of 1.2-1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, adjusted for individual needs. That translates to roughly 0.54-0.73 grams per pound.

I’m here for it.

Where things start to get messy is in the messaging.

The “war on protein” narrative doesn’t match reality. The “war on protein” is a boogeyman.

Protein has been the most consistently prioritized macronutrient in nutrition culture for well over a decade. It dominates fitness messaging, weight loss advice, aging research, and social media nutrition content. Most Americans already meet or exceed the protein RDA, and many actively aim higher.

The messaging creates a misleading impression that:

- Protein was previously minimized or suppressed

- Nutrition professionals were ignoring its importance

- This update represents a dramatic reversal rather than an incremental clarification

This is also where the pyramid imagery starts to break down.

While the written guidance emphasizes protein quantity and variety, the visual model prominently features several higher–saturated fat protein sources. When paired with encouragement of full-fat dairy and fats like butter or beef tallow, it creates tension with the unchanged recommendation to keep saturated fat below 10% of total calories.

Fats: Same limits, very different messaging

On paper, the 2025 Dietary Guidelines did not change the core quantitative recommendation for saturated fat.

The cap remains: Less than 10% of total daily calories from saturated fat.

Where things shift is not the number itself, but how foods that contribute saturated fat are emphasized and contextualized.

I don’t disagree with the idea that fats from whole foods can absolutely fit into a healthy diet.

Foods like nuts, seeds, seafood, olives, avocados, dairy, eggs, and meats all contribute fats alongside other nutrients.

I also agree that highly processed foods are a major driver of excess saturated fat intake for most people.

So far, so reasonable.

Where the guidance becomes harder to reconcile is in what’s emphasized without clear guardrails.

The 2025 guidelines explicitly highlight butter, beef tallow, full-fat dairy, and red meat as acceptable fat sources, while leaving the saturated fat cap unchanged. At the same time, they remove much of the practical guidance that previously helped people stay within that cap.

Earlier editions emphasized replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats, choosing oils more often than solid fats, and selecting leaner protein options as a way to make the math work. That substitution framework is largely absent in the 2025 guidance.

Dairy is a good example of this shift.

The recommended intake remains three servings per day, but the 2025 guidelines explicitly emphasize full-fat dairy, without the same focus on lower-fat or lactose-free options that appeared in prior editions. That change makes staying under the saturated fat limit more challenging in practice unless other sources are carefully adjusted.

The guidance around cooking fats adds another layer of confusion. The document advises prioritizing oils with “essential fatty acids,” naming olive oil as an example, while also stating that butter or beef tallow can be used. Olive oil has well-documented health benefits, but it is not a significant source of essential fatty acids in the way some vegetable oils are.

It’s also important to name why that saturated fat cap exists in the first place. We have decades of consistent evidence linking higher saturated fat intake to unfavorable lipid profiles and increased cardiovascular risk, particularly when saturated fats replace unsaturated fats in the diet. That evidence base is why the <10% recommendation has persisted across multiple guideline updates, even as other aspects of nutrition guidance have evolved. The science around saturated fat did not suddenly reset in 2025.

In real-world eating patterns, emphasizing full-fat dairy, butter, beef tallow, and red meat while keeping saturated fat below 10% requires tradeoffs that are not clearly articulated in the 2025 guidance.

The pyramid: where the messaging breaks down

The 2025 Dietary Guidelines present an inverted food pyramid as the primary visual model, positioning certain foods at the top to signal emphasis and priority. In theory, this is meant to communicate what to eat more of and what to build meals around.

In practice, the pyramid does not align well with the recommendations laid out elsewhere in the document.

Take whole grains. The written guidance recommends 2-4 servings per day, which is the highest serving range of any major food group. Under a traditional pyramid logic, that would place whole grains toward the top.

At the same time, foods emphasized higher up in the pyramid include red meat, full-fat dairy, butter, and beef tallow. Visually, this suggests prominence and desirability, even though consuming those foods at higher frequency makes it harder to stay within the unchanged saturated fat limit.

This creates a mixed message and it matters, because visuals are what most people remember.

Very few people will read the full text explaining serving sizes or nutrient caps.

They’ll see the pyramid, internalize what’s at the top, and assume that’s what they should be eating more of.

Added sugars and non-nutritive sweeteners

On the added sugar front, there’s very little here that’s controversial.

High intakes of added sugars are associated with poorer diet quality, increased cardiometabolic risk, and displacement of more nutrient-dense foods. From a public health perspective, encouraging people to limit added sugars makes sense. It always has.

The 2025 guidelines reinforce that message clearly. But they take it further.

They state clearly that “No amount of added sugars is recommended or considered part of a healthy or nutritious diet.”

And if, for whatever reason, you must include added sugar in your diet, they say that “One meal should contain no more than 10 grams of added sugars” and “Snack foods should adhere to FDA “Healthy” claim thresholds:

- Grain-based snacks should not exceed 5 grams of added sugar per ¾ ounce whole-grain equivalent

- Dairy-based snacks should not exceed 2.5 grams of added sugar per ⅔ cup equivalent

Sounds reasonable. We know sugar isn’t great for us.

Where things get complicated is when we move from recommendation to reality.

In today’s food environment, added sugars are everywhere. Not just in desserts and sweets, but in breads, sauces, yogurts, condiments, beverages, and foods marketed as “healthy.” Avoiding them entirely or keeping them consistently very low requires time, literacy, access, money, and control over food choices that many people simply don’t have.

That doesn’t mean the recommendation is wrong. It means it’s harder to implement than the guidance sometimes acknowledges.

This is also where I think the conversation around non-nutritive sweeteners needs more nuance.

The 2025 guidelines explicitly discourage low-calorie non-nutritive sweeteners, listing examples like aspartame, sucralose, saccharin, xylitol, and acesulfame potassium. Foods and beverages containing these ingredients are grouped alongside highly processed foods and added sugars as items to limit.

That framing is where the guidance starts to drift away from the evidence.

Current research does not support the idea that non-nutritive sweeteners are inherently harmful when consumed within typical intake ranges. They are not required for health, but they are also not equivalent to added sugars in terms of metabolic impact.

For many people, non-nutritive sweeteners function as a harm-reduction tool. This is especially true for:

- people with diabetes or insulin resistance

- individuals actively reducing added sugar intake

- people with a history of all-or-nothing dieting who benefit from flexibility rather than absolutes

Lumping non-nutritive sweeteners into the same “avoid” category as added sugars and highly processed foods removes an option that helps some people make meaningful, sustainable changes.

This is a recurring theme in the 2025 guidelines.

The recommendations themselves often make sense in isolation. The problem is the lack of nuance around how people actually eat, what tools they use to reduce risk, and what tradeoffs exist in real diets.

Encouraging lower added sugar intake is reasonable.

Framing sweetness as something that must be eliminated entirely, without acknowledging practical strategies people already use to get there, is where guidance shifts from helpful to inflexible.

“Guidance free from bias” vs conflicts of interest

A core theme in the rollout of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines is the promise of guidance “free from bias.”

That phrase shows up repeatedly, positioned as a corrective to prior editions and as justification for several of the framing choices in this update.

On its face, that sounds reassuring. Of course we want nutrition guidance grounded in sound science, not ideology.

The reality is, there’s no such thing as a completely bias-free guideline process.

The administration has emphasized that all conflicts of interest were disclosed in the development of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines. That’s true. Disclosure is required, and those disclosures were made.

However, disclosure is not the same as the absence of bias.

At the same time that the guidelines are being framed as a return to “scientific integrity” and freedom from the biases of past administrations, the list of contributors includes individuals with documented ties to industries such as supplements, dairy, cattle, and commercial diet programs (even though, RFK Jr himself said that the panel writing the new guidelines would have no conflicts of interest).

None of that automatically invalidates the science. Industry ties don’t inherently mean conclusions were fabricated or data was manipulated.

But it does mean that bias didn’t suddenly vanish in 2025. So why pretend like it has?

Conflicts of interest shape which questions get prioritized, which outcomes are emphasized, and which interpretations feel reasonable or “common sense.”

That’s true whether the influence comes from food companies, advocacy groups, academic institutions, or political leadership.

Most people don’t follow the guidelines anyway

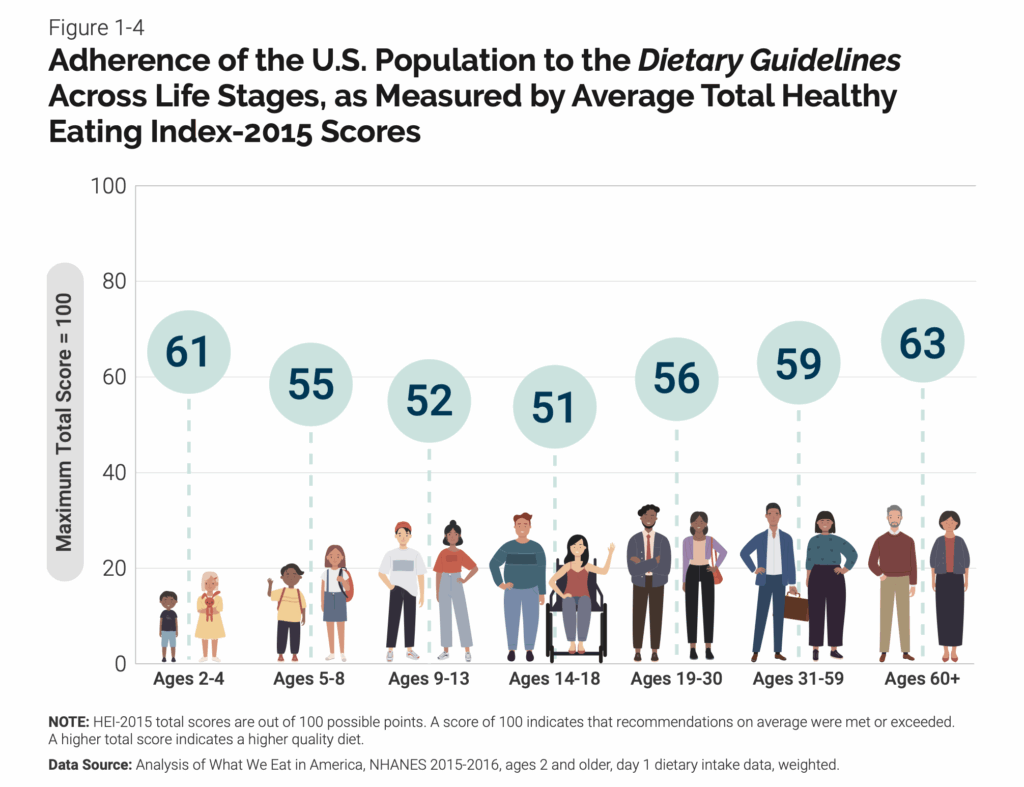

One thing that often gets lost in these debates is a much simpler reality: most Americans aren’t following any version of the Dietary Guidelines particularly closely.

At every life stage, average adherence to the Dietary Guidelines is around 50% or less.

The majority of Americans consistently fell short on vegetables, fruits, dairy, and healthy oils. Whole grain intake remained well below recommended levels. At the same time, most people exceeded recommended limits for saturated fat, added sugars, and sodium.

In other words, this isn’t a situation where people were carefully following the old guidelines and that’s why we have a chronic disease crisis in this country. The reality is… the gap between recommendations and real-world eating patterns is pretty freaking big.

If adherence has hovered around 50% or less for decades, making the guidelines more restrictive isn’t going to close that gap.

Telling people they shouldn’t even have a Diet Coke, despite evidence that non-nutritive sweeteners can be a useful harm-reduction tool for some individuals, isn’t helpful.

When people feel like everything they enjoy is “wrong,” they’re much less likely to try making any changes at all.

Instead, we should be asking:

“How do we help people actually do the things we’re recommending?”

“How do we invest in programs that make healthier choices easier, more accessible, and more realistic?”

“How do we improve nutrition literacy so people understand not just what to eat, but why and how to apply it in real life?”

It’s hard to argue that stricter guidance is the missing piece when nutrition education is still optional in most school systems. There are no universal requirements to teach basic food skills, label literacy, or how to build meals. We expect adults to navigate a complex food environment without ever having been taught how.

If adherence has been low across every version of the guidelines, the solution isn’t drawing harder lines around “good” and “bad” foods. It’s addressing the systems that determine whether people can realistically meet the guidance at all.

So where does that leave us?

With guidelines that are not wildly different from prior editions.

With guidelines that aren’t wildly different from prior editions. And a lot of people in health and nutrition using them as an excuse to dunk on each other instead of actually helping anyone.

And if we care about improving public health, the most productive question isn’t “Who won this update?”

It’s whether the guidance helps people, programs, and practitioners make better decisions in the real world.

That’s still an open question.

References

Watch The Press Release

2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

2025-2030 Daily Servings Guide

Scientific Foundation For the Dietary Guidelines

The Scientific Foundation For The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines For Americans Appendices

1980 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

1985 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

1990 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

1995 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

2000 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

MyPlate

2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans