Lately, sourdough bread has been making a huge comeback. This age-old tradition, which dates back to the Egyptians around 1500 BC as one of the first uses of leavening, is now making its way to our social media feeds via your favorite influencer.

The current fascination with sourdough among wellness influencers may have started as a fun thing to do during the Covid-19 lockdowns but can also be attributed to a growing interest in returning to more traditional, slower ways of living. This trend reflects a broader cultural shift toward seeking out more ‘natural’ dietary choices, positioning sourdough not just as a food, but as a lifestyle emblematic of a healthier, more mindful way of living.

Platforms like Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok are buzzing with sourdough starter tutorials, tips, and aesthetically pleasing photos of perfectly baked loaves. The same influencers who wouldn’t have touched a carbohydrate a few years ago are now singing the praises of sourdough for it’s simple ingredients and gut health benefits. Some even claim that sourdough is the only bread they can tolerate while others just view it as a “cleaner” alternative to more processed, store-bought breads.

But beyond the trendy instagram picture, is sourdough bread truly healthier than other types of bread? In this blog post, I’ll break down the health claims surrounding sourdough bread to see if the research supports them. We’ll compare its nutritional content to other popular bread types and explore the science behind whether the sourdough craze might be more than just a trend.

Nutritional Comparison: Sourdough vs. Other Breads

Homemade sourdough is typically made with a few simple ingredients:

- Flour: Can be made from various types of flour, including whole wheat, rye, spelt, or all-purpose flour. Whole grain flours offer a higher fiber and nutrient content.

- Water: Hydrates the flour, activates the enzymes and yeast in the sourdough starter, and helps form the dough.

- Salt: Enhances flavor and strengthens the gluten network, contributing to the bread’s structure.

- Sourdough Starter: A natural leavening agent that contains wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. The starter is a live culture of flour and water.

Commercial versions of sourdough may include additional ingredients to enhance shelf life, texture, and flavor, such as preservatives, emulsifiers, and added sugars. These additives can affect the overall nutritional quality.

Creating a sourdough starter involves mixing equal parts of flour and water and then nurturing it. This involves daily feedings over the course of the week until it’s bubbly and aromatic, indicating that it’s ready to use for baking.

The fermentation process in sourdough involves two key microorganisms: wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria. Wild yeast, naturally present in the environment and the flour, acts as a leavening agent by producing bubbles of carbon dioxide that cause the dough to rise. Lactic acid bacteria, on the other hand, produce lactic acid and acetic acid. These acids not only give sourdough its distinctive tangy flavor but also contribute to the bread’s unique texture and extended shelf life by acting as natural preservatives.

Like other bread, sourdough is primarily a carbohydrate-based food with very minimal protein and fat. The fiber content can vary, with whole wheat versions packing more dietary fiber than those made from refined flour.

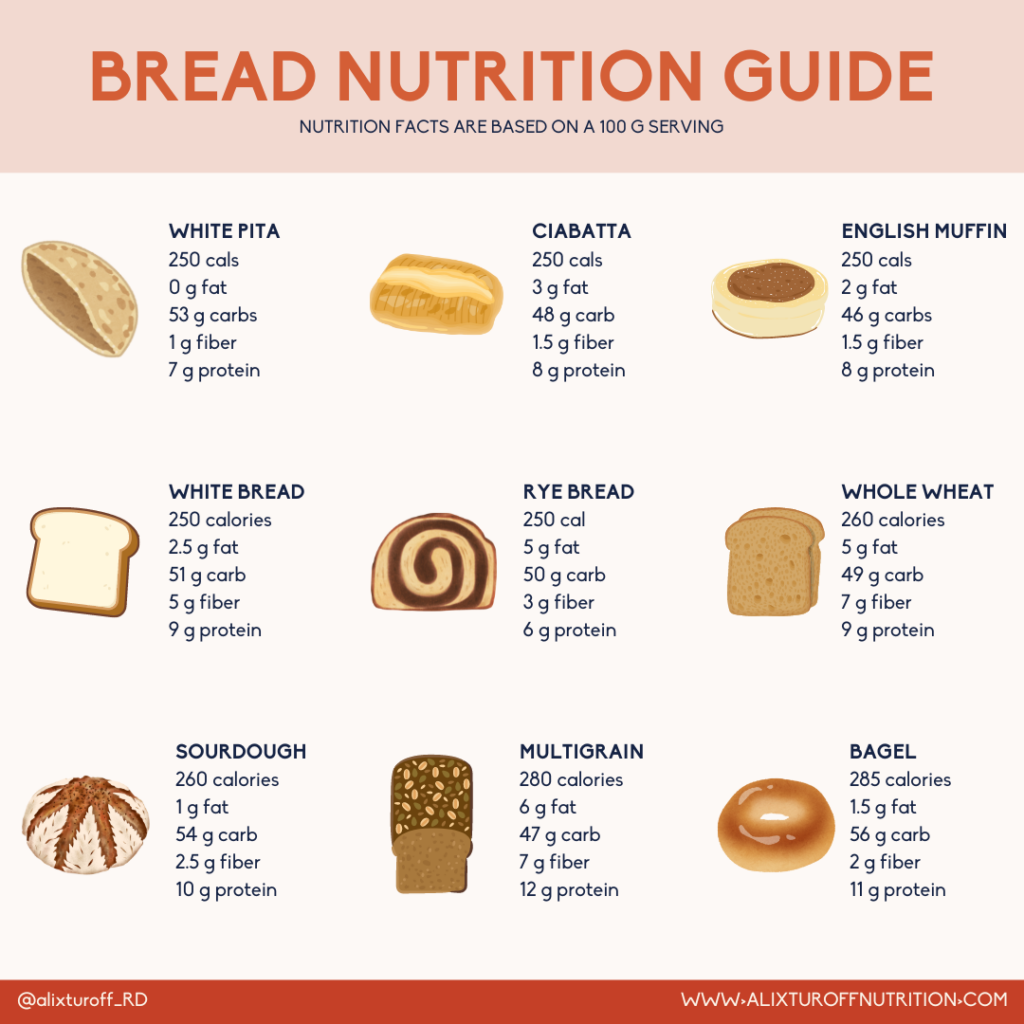

To understand how sourdough compares to other types of bread, I selected a variety of common bread types that are widely consumed and easily accessible. This selection includes white pita, ciabatta, English muffin, white bread, rye bread, whole wheat bread, sourdough, multigrain bread, and bagels.

For each type of bread, I gathered multiple nutritional profiles from different brands and products to account for variations in recipes and ingredients. I focused on key nutritional components: calories, fat, carbohydrates, fiber, and protein. I sourced the nutritional information from USDA FoodData Central, nutrition labels from commercial bread products, and trusted online nutrition websites.

To ensure the data is representative, I calculated the average values for each nutritional component across the different sources and brands for each type of bread.

All nutritional facts are based on a standardized 100-gram serving size to allow for direct comparison between different types of bread. This uniform measurement makes it easier to compare and contrast the nutritional profiles.

Here is what I found:

This infographic lays out the calories, carbs, fiber, and protein for each bread type based on a 100-gram serving. I found that the basic nutrition facts across different bread categories are quite similar so sourdough didn’t necessarily stand out as a particularly lower calorie or lower carb choice.

Despite these similarities, sourdough bread is often touted for its unique health benefits. In the next section we’ll look out the most common health claims that are made about sourdough and we’ll examine the scientific research to see if it supports those claims.

Health Benefits of Sourdough Bread

Now that we’ve looked at the calorie and macronutrient differences between sourdough and other breads, it’s time to explore some of the claims that are most commonly attributed to sourdough bread. I’ve broken these claims down into five categories and from there, we’ll explore what the research says.

The most common claims that are made when it comes to the health benefits of sourdough over other breads are:

- Improved Glycemic Response: Sourdough bread is often touted for its lower glycemic index,

which suggests it may lead to a slower rise in blood sugar levels post-consumption, a benefit attributed to its unique fermentation process.

- Enhanced Nutrient Bioavailability: Sourdough fermentation is believed to reduce phytates that inhibit mineral absorption, potentially enhancing the availability of minerals like magnesium, iron, and zinc.

- Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Properties: Some research suggests that sourdough fermentation might increase the bread’s antioxidant levels, contributing to reduced oxidative stress and inflammation, potentially benefiting overall health and conditions like arthritis.

- Digestion and Gut Health: Sourdough’s fermentation process breaks down gluten and other proteins, which may make it easier to digest, especially for those with mild gluten sensitivities. It’s also suggested that the lactic acid bacteria in sourdough act as probiotics, enhancing gut health.

- Reduced Need for Preservatives: Sourdough bread is often claimed to have a longer shelf life compared to other breads. Thanks to the organic acids produced during fermentation, sourdough is thought to resist mold and spoilage, potentially reducing the need for chemical preservatives.

Now, let’s explore each of these claims in depth, examining the available scientific evidence to see how sourdough truly measures up against more conventional breads.

Improved Glycemic Response

The majority of research suggests that sourdough bread generally leads to a lower glycemic response compared to breads made with commercial yeast. Studies by Maioli et al. (2008) and Scazzina et al. (2009) found that sourdough bread leads to significantly lower blood sugar and insulin spikes post-eating. This benefit is often attributed to the fermentation process, which increases resistant starch and decreases simple sugars. However, some studies, such as those by Mofidi et al. (2012) and Korem et al. (2017), indicate that the glycemic response to sourdough can vary significantly between individuals and depend heavily on the specific sourdough formulation, indicating that not all sourdough breads offer the same benefits. Overall, while sourdough bread often provides a lower glycemic response, individual factors and specific formulations can influence the extent of this benefit.

Enhanced Nutrient Bioavailability

Research consistently shows that sourdough bread enhances the bioavailability of essential nutrients compared to other types of bread. Studies by Lopez et al. (2003) and Poutanen et al. (2009) found that sourdough fermentation enhances the absorption of minerals such as magnesium, iron, and zinc by reducing the phytate content, which normally inhibits mineral absorption. Although most studies confirm the positive impact of sourdough on nutrient bioavailability, the degree of improvement can depend on the type of grain used. Additionally, while certain nutrients may be more bioavailable in sourdough, the total vitamin and mineral content in sourdough may not be as high as in fortified or whole grain breads.

Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Properties

The majority of research supports the claim that sourdough may offer enhanced antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits over other breads. Studies such as those by Luti et al. (2020) and Galli et al. (2018) have shown that sourdough fermentation can significantly boost the production of bioactive peptides and antioxidants, helping to mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation. Further research by Kwon et al. (2022) links sourdough to reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and improved gut health in animal models. However, some studies, such as those by Irakli et al. (2019) and Laatikainen et al. (2017), found that these benefits can vary based on factors like grain type, fermentation specifics, and individual health conditions, highlighting that while sourdough generally promotes a better antioxidant and anti-inflammatory profile, the extent of these effects can differ.

Digestion and Gut Health

Studies show that sourdough fermentation positively impacts gut microbiota composition, increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria by increasing beneficial bacteria like Akkermansia and Lactobacillus and boosting the production of short-chain fatty acids, crucial for colon health. Additionally, sourdough is easier to digest due to faster gastric emptying, alleviating gastrointestinal discomfort. However, some studies, like those by Laatikainen et al. (2017), suggest that these benefits can vary depending on individual health conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), where sourdough did not significantly improve symptoms compared to yeast-fermented bread. Overall, while sourdough bread generally promotes better digestion and gut health, its effectiveness may vary based on personal health factors.

Reduced Need for Preservatives

Sourdough bread often requires fewer chemical preservatives due to its natural fermentation process. Studies by Quattrini et al. (2019) and Belz et al. (2019) have shown that specific lactobacilli strains in sourdough produce natural acids that inhibit mold and extend shelf life, potentially reducing or eliminating the need for synthetic preservatives. However, some studies, such as those by Ryan et al. (2008) and Axel et al. (2016) note that sourdough’s preservation abilities may vary, especially against certain fungi or in gluten-free options, suggesting a minimal use of chemical preservatives might still be necessary in some cases. Overall, sourdough fermentation enhances the shelf life of bread and reduces the reliance on chemical additives, making it a cleaner and more natural option.

Conclusion

So while sourdough is currently having it’s moment on social media, it does seem to have some unique health benefits that go beyond calorie and macronutrient content which can be attributed to the fermentation process.

- Better Blood Sugar Control: Research often points to sourdough having a lower glycemic index, which helps manage blood sugar levels more effectively.

- Increased Nutrient Absorption: The fermentation process enhances the bioavailability of minerals such as iron, magnesium, and zinc by breaking down phytate barriers.

- Antioxidant Boost: Fermenting dough increases its antioxidant levels, potentially reducing inflammation and improving health.

- Digestion and Gut Health: Sourdough’s breakdown of gluten makes it easier on the stomach, with properties that benefit gut health and digestion.

- Fewer Additives: The longevity of sourdough is naturally extended by organic acids from fermentation, reducing the need for added preservatives.

However, there are some caveats to consider:

- Variability in Commercial Sourdough: Not all commercially available sourdough bread undergoes traditional fermentation, which can affect its health benefits. They also might contain added preservatives and enhancers to improve taste and extend shelf-life.

- Not for Celiac Sufferers: While some individuals with gluten sensitivity might find sourdough easier to tolerate, it is not suitable for those with celiac disease. Sourdough bread still contains gluten and can cause adverse reactions in individuals with celiac disease.

- Weight Management: For those focusing on weight management, sourdough bread is nutritionally equivalent to other breads and may even be less ideal due to its lower fiber content compared to whole grain or multigrain breads. Fiber is important for satiety and digestive health, so those aiming to increase fiber intake might prefer other bread types.

Overall, while sourdough is still a carbohydrate source with roughly the same amount of calories as other breads, the fermentation process offers a few distinct health benefits making it a worthy addition to a balanced diet. That being said, other types of bread may be a better option if you’re looking for fiber and although the nutrients in sourdough might be more easily digested, the overall nutrient content is lower than other fortified breads. Sourdough bread is certainly a good option and it does have some unique benefits but it’s not leaps and bounds better than other types of bread.